The following is an excerpt from a book by Richard A. Shaefer about Loma Linda University, The Glory of the Vision (expected publication date: 2011).

Section I: How Can We Do Research?

The First Steps Forward1

For the first two decades of its existence, Loma Linda University did not prioritize research. Instead, corporate energy had to be directed toward establishing the institution, defining its purpose and direction, and developing curricula in nursing, medicine, and dietetics. Despite worrisome financial uncertainties hovering in the background, men and women of vision, dedication, and faith managed—over time—to create the College of Medical Evangelists.

The second decade brought grave concerns about the very survival of the School of Medicine. When the American Medical Association (AMA) evaluated medical schools throughout the United States, they determined that only those rated “A” would be allowed to continue. This recognition finally came in 1922. Relief from the pressures of uncertainty enabled Administration and Faculty to concentrate on the growth and quality of education. Lack of adequate finances, however, always shadowed the small institution.

Involvement in research and excellence in teaching at LLU is rooted in the third decade of Loma Linda’s development. The youthful perspectives brought by new professors (recent graduates) in the School of Medicine largely accounted for this turn of events.

The Harveian Society

The Harveian Society was established in 1928, primarily under the leadership and enthusiasm of G. Mosser Taylor (Class of 1924) and Cyril B. Courville (Class of 1925). According to its constitution, “The general aim of the Harveian Society is to develop the scholarly attainments of this school in a way to achieve the high standard reached by Daniel and his comrades in the golden days of old Babylon. Also, in a very definite manner, to demonstrate irrefutably that one may hold by faith to spiritual truths and at the same time be exact scientifically.”

Specific goals of the society were:

- To stimulate research,

- To advance medical educational methods,

- To develop a higher type of graduate, and

- To encourage the highest type of graduate to join the faculty of CME.

The name “Harveian” was chosen because it suggested a “scientific society associated with research.”2 Membership in the society was open to any faculty member or graduate of CME. Active membership, however, had specific requirements:

- To prepare one paper per year acceptable for publication,

- To facilitate improvement in teaching,

- To be knowledgeable about current literature in one’s field, and

- To abstract important articles on a monthly basis.

These abstracts were presented at monthly society meetings, and some of them were published in the weekly issues of The Medical Evangelist (until 1936). When The Journal of the Alumni Association College of Medical Evangelists (Alumni Journal) began in 1931, occasional abstracts appeared there also.

The first meeting of the Society took place on September 18, 1928.3 Regular society meetings convened thereafter on the third Tuesday evening of the month (except July and August). The venue alternated between the Loma Linda and Los Angeles campuses.

Finances and Honors. The Harveian Society actively encouraged School of Medicine alumni to support research projects by donating on a regular basis. The School of Medicine Alumni Association created the Alumni Research Fund in order to foster their members’ involvement. Nonetheless, it was an uphill climb. Frequent pleas arose, begging for more vigorous support. H. James Hara (Class of 1918) suggested that all alumni donate a dollar a year for each year since their graduation.

Another Society activity promoted the recognition of high achievement by students. For instance, the Heritage Room has a copy of a book inscribed: “Presented to Carrol S. Small, MD, by The Harveian Society of the College of Medical Evangelists in recognition of the excellent scholarship he attained on National Board of Medical Examinations.”

Publications. In 1939 the Society began publishing the Harveian Review, a journal edited by Charles B. Coggin (Class of 1935).4 Other editors included Dr. Carrol S. Small (Associate Editor). Also, Lloyd K. Rosenvold (Class of 1936); and William C. Bradbury (Class of 1935) served as Managing Editors.

Lead articles and editorials often described the value of research. Two columns appeared on a fairly regular basis: “Recent Publications by Society Members” and “Clinical Notes.” The latter were abstracts of “new advances in medical practice.” There were also short articles on various subjects such as medical topics, reports of research, and news affecting the school. Although the journal called itself a quarterly, seven issues appeared in the first volume and two in the second. The last issue in library archives is dated August 1941.5

The Harveian Society and Harveian Review faded from sight after 1941. World War II engulfed the world, with the U.S. a participant by December 1941. Many of the Society’s active supporters now wore military uniforms, soon to be scattered about the globe. Once again, CME fought for survival. This time the struggle was to retain adequate faculty and to make certain that students were graduated before being drafted.

Although it existed for only thirteen years, the Harveian Society raised the consciousness of the institution about research. To be sure, there was no groundswell of support. Many faculty members either could not see the value of research or felt that they did not have the time to do it. Moreover, the continuing need for funding meant frequent appeals to alumni and others, often with disappointing results.

Nonetheless, one could see a few flickers of hope. In 1936, new laboratory buildings in which research took place were constructed on campus (anatomy and pathology). A brief collaboration with the W. K. Kellogg Foundation brought in new equipment and personnel. Alumni gave financial support. Research accomplishments were often listed in The Medical Evangelist and the Alumni Journal. In 1941 March of CME announced that from the time the Harveian Society began the following works had been produced: “Ninety major studies, forty-four case reports and clinical notes, and twelve technical notes in addition to a textbook and five medical monographs.”6

The challenges and triumphs of these early stalwarts of research at LLU may sound unfamiliar to us sixty years later. In contrast, in today’s academic setting, the vital importance of research is recognized. Now the specialists do the fund-raising and grant applications. Still, we must salute the members of the Harveian Society for their early vision and seed sowing.

We Entertain the Idea of Research

Awareness. Since the beginning, CME's team of educators drew eagerly but passively from the general fund of medical knowledge contributed by men and women who had researched and experienced what they needed to know.

Having no faculty engaged in basic research was perceived as a deficiency. The CME faculty and administration recognized that the School's on-going accreditation depended on their developing programs of scientific research. CME, however, continued to operate under the handicap of meager finances, primitive equipment, and almost non-existent research assistants. Ongoing and heavy teaching responsibilities detracted the professional staff from engaging in much-needed research.

In 1937 Harold Shryock, MD, the future dean who had once been a full-time research assistant, enrolled at Harvard University for a six-week elective course, "Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology.” Following the lecture each day, one of his anatomy professors would disappear into a laboratory to engage in a personal research project. One afternoon Shryock caught up with him in the hallway. "Professor," he called. "I have a great interest in promoting research where I work at the College of Medical Evangelists. What future training do I need in order to do my own research?

The man turned and asked, “You're a physician, aren’t you?”

“Yes.”

“What more training do you need?”

With that the professor continued on his way, leaving Shryock to absorb what he'd just been told. The message was clear. "Get to work with what you have." The man's words served to motivate Dr. Shryock for many years to come.

Stepping Forward. Dr. Shryock firmly believed that an ongoing research program would stimulate the faculty, improve the quality of teaching, and increase the students' appreciation for their school. On the other hand, maintaining the status quo would lead to an inferior grade of medical education. He observed that other institutions that were scientifically productive, thanks to private funding, were beginning to overshadow his beloved CME. Private funding appeared to be making the difference.

Wanting to help correct CME’s weakness, Shryock tried in his own way to conduct basic research projects. His efforts resulted in fifteen published scientific articles in the areas of cytogenesis (the formation of cells) and congenital anomalies of the nervous system. Co-authors included CME alumni, a resident physician at the Los Angeles County General Hospital, and CME faculty colleagues. In several instances, Shryock involved students and proudly published their names as participants.

Some of the articles reported congenital anomalies researched in the CME Department of Anatomy, including an illustrated description of methods developed in Loma Linda to help medical students visualize the internal features of the human brain. The American Association of Anatomists admitted Harold Shryock to membership on the strength of that article alone.

Almost from the beginning, the School of Dentistry administration recognized the value of research in educating student dentists and in improving patient care. In 1956, three years after the School had opened, Dean M. Webster Prince acknowledged that his teaching faculty had insufficient time for research. To remedy the problem he immediately started working to secure more full-time faculty to share the teaching load.7

When the School’s new building opened in 1955, two major research rooms were created, one for biological research and one for dental materials. In addition, a small research area adjoined each faculty member’s private office. Thus teachers could take an active part and develop their ongoing interests in the context of the School’s research program.

Ten Research Specialties

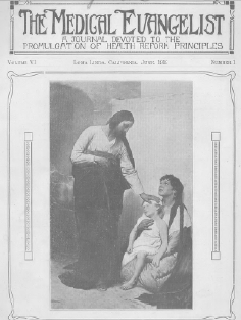

1. TURP. Roger W. Barnes, MD

Roger W. Barnes (Class of 1922), developed a surgical procedure that has been most widely used throughout the world. The device deals with obstructions in the flow of urine because of the enlargement of the prostate gland.

Dr. Barnes enhanced and popularized the trans-urethral resection of the prostate (TURP) on the Los Angeles campus of the College of Medical Evangelists. The procedure has had a major impact on patient care over many years.8

2. Pain Control: Dr. Niels Bjorn Jorgensen, DDS

Today, Loma Linda University School of Dentistry owes much of its international reputation to a technique of dental pain control. Niels Björn Jörgensen, a specialist in local anesthesia and sedation developed it.9 His technique, which can be used in any branch of dentistry, involves intravenous sedation in conjunction with a local anesthetic to reduce patient apprehension and fear. This sedation technique allows the patient to hear and respond rationally.10

While general anesthesia puts the patient to sleep, the "Loma Linda Technique" maintains the patient's protective cough reflex and allows cooperation with the dentist. It individualizes the dosage of the medication, administering it in small increments, according to the patient's response. Dr. Jörgensen promoted the designation "Loma Linda Technique" (rather than the "Jörgensen Technique" as it is known by many of his peers). Forrest E. Leffingwell, MD (Class of 1933) "incalculably aided" Dr. Jörgensen.11

Dr. Jörgensen's teaching film, "Inferior Alveolar, Lingual and Buccal Nerve Block," won the "1st Grand Prix." The International Dental Film Competition in Paris in March 1965, judged it best, among the seventy films submitted. In all, Dr. Jörgensen made nine films. Schools of dentistry around the world used these classics for years. They were translated into other languages and kept in constant circulation by the Bureau of Audio-Visual Services of the American Dental Association. Dr. Jörgensen's textbook, Sedation, Local and General Anesthesia in Dentistry (published in 1966), was distributed throughout the United States, Western Europe, and South America.

Dr. Jörgensen's teaching program at Loma Linda University anticipated by at least fifteen years most of the recommendations in the Guidelines for Teaching the Comprehensive Control of Pain and Anxiety in Dentistry (1971). The American Dental Association published his book in 1971. In 1960 Dr. Jorgensen won the prestigious Heidbrink Award, presented by the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology. In 1966 he received the John Mordaunt Prize, the highest honor of the British Society for the Advancement of Anesthesiology in Dentistry, being its sole recipient until his death in 1974.

Norman Trieger, DMD, MD, editor of the Journal of Anesthesia Progress (the official publication of the American Dental Society of Anesthesiology) referred to Dr. Jörgensen as "one of the giants in anesthesiology in dentistry, and in particular, in the education of the undergraduate student...[in the technique of] sedation."12 The National Institutes of Health based its guidelines for pain control on the Jorgensen Technique.13

Dr. Jörgensen came to the United States in 1919 after completing pre-medicine studies in his native Denmark. In 1923 he earned his Doctor of Dental Surgery degree from the University of California School of Dentistry. Dr. Jörgensen joined the faculty of Loma Linda University, first in 1942 as an Associate Professor in the School of Medicine. At that time, he began his studies into sedation for pain control, mainly related to nerve blocks in the neck and skull. He eventually joined the School of Dentistry faculty as professor. He also invented a self-aspirating carpule syringe, a significant protection against ultra vascular injection. After thirty-two years on the faculty of Loma Linda University, he retired in 1969. Still, he continued to be active in the School of Dentistry as Emeritus Professor of Oral Surgery, where he continued teaching dental students his methods of pain control.

According to the School of Dentistry’s third dean, Dr. Judson Klooster, “Dr. Jörgensen’s contribution to the dental profession will go down in history as one of the giant steps which took dentistry out of the aboriginal woods. We feel fortunate to have benefited from his professional expertise and the inspiration of his personal life.”14

At the 1971 President’s Convocation, President David J. Bieber presented Dr. Jorgensen with a plaque honoring him for his major scientific contributions to Loma Linda University.

In response, Dr. Jorgensen wrote: I have received many plaques, but none as precious to me as this one…. Loma Linda has from the beginning been of great importance in my life, and in spite of my accent, not being a born American and being raised in a different church, I have met so much cooperation and kindness from everybody: administration, faculty, students, and alumni, that I am the one who has been the recipient from this University.”15

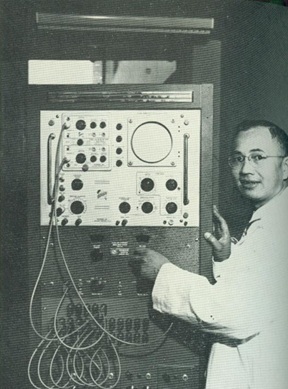

3. Fetal Monitoring: Edward H. G. Hon, MD

The fetal monitor is an electronic instrument that assesses the condition of the fetus before birth. Its use significantly reduces the dangers associated with childbirth. Edward H. G. Hon, (Class of 1950), pioneered fetal monitoring. With an extensive background in electronics engineering, he initiated his research in 1955 as a member of the faculty at Yale University. He continued his research at the White Memorial Medical Center (1960-1964) and again at Yale, where he developed the world's first fetal intensive care unit (1969).16

The device made monitoring the heart rate of the unborn infant a simple procedure. The obstetrician can now hear the fetal heart rate continuously, even during labor contractions. In addition, the monitor enables obstetricians to measure the strength and frequency of uterine contractions. The evaluation of fetal heart rate and uterine contractions together provides information about the condition of the unborn infant and how well it tolerates labor. This information helps prevent complications during labor and delivery which otherwise could lead to fetal damage and death.17

According to Dr. Hon, a baby’s heartbeat is usually between 120 and 160 beats a minute. “For a physician to obtain any meaningful check, he must count those beats frequently and accurately. Few can do this during labor without significant error. Of course, the greater the error, the more inaccurate the count.” Dr. Hon’s fetal heart rate monitor provides accurate, continuous records of fetal heart rate throughout labor and delivery.18

Life magazine featured Dr. Hon in 1969, while he still worked at Yale University. Between 1956 and the Life report, he had monitored over 3,000 births, including that of his own son. Explaining monitoring and its importance, Life magazine described the event:

The fetus must struggle to survive the strains and pressures being put upon it. For years attending doctors have had no reliable way -- nothing better than a stethoscope -- to tell precisely when the fetus was in trouble. Consequently, some five to seven infants per thousand die unexpectedly each year.

The instant a baby gets into trouble -- a squeezed umbilical cord, a compressed head or a shortage of oxygen -- its heart reflects a precipitous fall on the machine's graph. Fortunately, 90% of all fetal distress is caused by umbilical cord compression. Once spotted, it can usually be relieved by simply changing the mother's position.

When the unit…was tried on four hundred mothers with histories of difficult labor, the results were impressive. None of the babies died, the number of Caesarean sections for fetal distress was reduced by 75%, and the number of injured babies was cut by 50%. Hopefully, Dr. Hon's new system could save as many as 20,000 babies a year.19

Fetal monitoring dramatically enhances good obstetrical care in hospitals and clinics around the world. It has reduced fetal death and brain damage during labor. Dr. Hon’s fetal monitoring system was first installed at Loma Linda University Hospital in late 1968.20

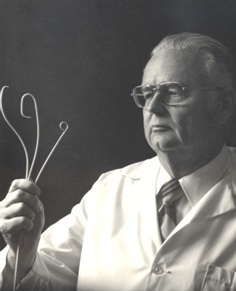

4. Selective Coronary Arteriography: Melvin P Judkins, MD

In 1966 Melvin P. Judkins (Class of 1947), introduced the Judkins Technique of Coronary Arteriography, which creates X-ray pictures of the blood vessels of the heart. While he did not originate coronary arteriography, Judkins’ technique and ingenious catheter designs greatly simplified the procedure. Instead of obtaining patents for his inventions, which would have made him extremely wealthy, he gave them to the world of medical science.

During the procedure, a radiologist eases a tiny hollow plastic tube (about the diameter of the lead in a large pencil) up the large artery of one of the legs, first to the aorta and then, in turn, to the left and right coronary arteries. In each location of study colorless liquid called “contrast” is injected through the tube (vascular catheter) into the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle, making them visible on X-ray film. The patient’s physician is thus able to see the exact location and extent of any disease. These pictures then make it possible for cardiologists and heart surgeons to select the preferred method of treatment. This procedure brings relief of pain and extends life for many coronary arteriosclerosis victims.

Dr. Judkins was a perfectionist and, according to former students, an excellent teacher. He played an important role in the training of the next generation of physicians in the management of his technique. He also created state-of-the-art cardiovascular laboratories at LLUMC.

Until his death in 1985, Dr. Judkins was recognized internationally as an authority on radiologic equipmentand on the diagnosis of coronary artery disease. He would now be delighted to see the advancesthat have been made in recent years in the treatment of coronary disease. New catheters based on hisdesigns are regularly used to introduce balloons and stints into coronary arteries to indirectly relieve blockages.

The Judkins Technique of Coronary Arteriography is recognized internationally as a major contribution to world medicine.

5. A Fluid Transport System and the Prevention of Tooth Decay: Ralph R. Steinman, DDS, MS, & John Leonora, PhD

Ralph R. Steinman, Professor of Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, and John Leonora, Professor of Physiology and Biophysics, School of Medicine, made important discoveries in 1971. They demonstrated a change in fluid dynamics within teeth: a transport system flowing from the pulp through the dentinal tubules that is impacted by the presence of sugar.

Dr. Steinman had studied the dental literature back to the 1880’s and had discovered an interesting minority view based on research indicating that teeth might possess a defensive mechanism against cavities. This information motivated Dr. Steinman to explore the theory. He developed a rapid technique to visualize dentinal fluid flow using fluorescent dye as a marker. By tracking the dye, Dr. Steinman was able to document an astounding observation: that teeth are internally active. In the absence of sugar, the dentinal fluid flowed within the tooth from the dentin-pulp interface through the dentin. In contrast, no significant flow occurred in the presence of a high sugar intake. The fact that sugar in the diet could affect an internal process in teeth had not been documented before.

The discovery had important implications regarding the eventual prevention of dental decay. The significance of the outward dentinal fluid flow is that: (1) It prevents the penetration of bacterial acids into the tooth structure, and (2) it neutralizes the bacterial acids on the surface of the teeth.

To answer the question of how this mechanism was controlled, Dr. Steinman consulted with Dr. Leonora who suggested that a hormonal mechanism would be most appropriate for controlling dentinal fluid flow. Their collaborative studies led to the discovery of a new endocrine system: the hypothalamic-parotid gland endocrine axis. They isolated the parotid hormone in a pure form, and showed that it stimulates dentinal fluid flow. They demonstrated that a high sugar diet suppresses the function of this endocrine axis and consequently dentinal fluid flow. They continued their research to demonstrate in rats that they could physiologically prevent the suppressive effect of the high sugar diet on dentinal fluid flow and prevent dental decay 80% to 100% of the time.

Subsequent research by others has concluded that dentinal fluid flow also exists in human teeth. Therefore, dentinal fluid flow may be an important defensive mechanism for preventing dental decay in humans.21

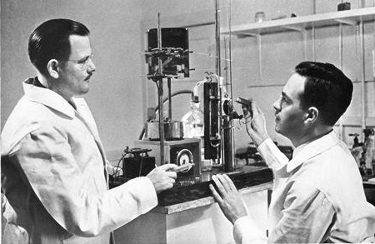

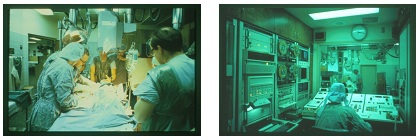

6. Computerized Radiation Therapy Planning: James M. Slater, MD

Advances in the development of radiation therapy equipment has greatly enhanced the capabilities of the physician who specializes in cancer treatment (the radiation oncologist) and the radiation physicist. A wide variety of equipment now available can produce well-defined beams of radiation of infinitely varied shapes and sizes. Physicians can now deliver precise doses of radiation to specific tumor sites to retard or stop tumor growth.22

Radiation, however, can damage healthy as well as diseased tissues. To minimize the harmful effects, the radiation oncologist and the radiation physicist together plan a program of therapy. One that will deliver therapeutic doses of radiation to the site of deep tumors with minimum damage to surrounding areas.

For the patient's safety, precise measurements and careful planning are extremely important. Such procedures can be complex and time-consuming. Under the direction of James M. Slater (Class of 1963), scientists began to simplify and speed up the making of such a treatment plan. In 1974 they developed a computer-based radiation therapy planning system, using an ultrasound scanning device and a color video screen.

.jpg)

This radiation treatment planning system can accept patient data from ultrasound scans, diagnostic x-rays, radioactive isotope scans, computerized tomographic (CT) scans, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans, and other sources. In essence, it brings together in one integrated, computerized unit all the electronic and technical hardware and all the diagnostic and anatomical treatment planning tools of the cancer treatment specialists.

As compared with older methods, this system provides a much more rapid and accurate evaluation of possible treatment alternatives. It also enables the therapist to determine the best possible radiation dose-distribution pattern for the individual patient¾and much more quickly. All the patient’s information is immediately available, and the computer can process it instantly.

This system can record accumulated dose-distributions for patients who have been treated under several different treatment plans. Thus the treatment specialist knows the total amount of radiation to which the target and surrounding area have been exposed.

Although today leading hospitals use similar integrated radiation therapy planning systems, Dr. Slater pioneered interfacing diagnostic tools with the computer in what is now one of the most versatile and complete systems in the world.

Chosen to be members of the United States delegation to Vienna, Austria, in March 1975, Dr. Slater and William T. Chu, PhD, presented their research in developing this system to the International Atomic Energy Agency Symposium of Advances in Biomedical Dosimetry. Their exhibit entitled "Computerized Radiotherapy Planning System" won first prize at the Third International European Congress of Radiologists, held in Edinburgh, Scotland, in June 1975.23

7. Fetal Studies: Lawrence D. Longo, MD

Lawrence D. Longo (Class of 1954), Distinguished Professor of Physiology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, has explored various aspects of fetal studies. For instance, the dynamics and regulation of respiratory gas exchange in the placenta and oxygenation of the fetus. This has included work on the interaction of the fetal cardiovascular and endocrine systems and mathematical modeling of oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange. In addition, he has concentrated on several aspects of oxygenation and brain development in the fetus and newborn infant.

These studies have included cellular markers for hypoxia, and the role of hypoxia-ischemia on gene expression in the developing brain. In conjunction with these studies, Dr. Longo wrote the section in the Surgeon General’s Report on smoking and health hazards to the mother and fetus. He also played a key role in legislation that required warning labels on cigarette packages.24 Dr. Longo has served in many influential professional groups.25

During the past decade, most of Dr. Longo’s efforts have concentrated on exploring basic biochemical mechanisms of signal transduction in cerebral arteries. How do these change with development from fetus to newborn to adult, and in response to long-term hypoxia. The goal of these studies has been to integrate knowledge of cerebrovascular regulation at the cell and molecular level. Also, he investigated in vivo studies on the role of regulation by the various enzymes and the role of free radicals in reperfusion injury. Then all of this had to be translated to the bedside in the improved management of the premature infant with dysregulation of cerebral blood flow.

Some of the questions Dr. Longo and his associates address are:

- Why are some infants born with cerebral palsy, mental retardation, epilepsy, and other disorders?

- What is the biochemical basis for these developmental abnormalities?

- Why are infants who are malnourished or anemic, who live at high altitude or whose mothers smoke smaller than normal?

- What are the biological implications of their growth retardation?

- How can the fetal and newborn cerebral blood vessels be regulated, so as to deliver oxygenated blood optimally?

In 1988 Dr. Longo received a NATO professorship from the Scientific Research Council of the Italian government. Additionally, he has published a number of papers on various aspects of the history of obstetrics and gynecology, particularly during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He is the author of more than 300 scientific papers and nine books.

In 1996 Dr. Longo received awards from two prestigious organizations, the Society of Gynecologic Investigation and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Great Britain. In response, he gave credit to his team:

"I feel a little embarrassed talking about this, but I am proud of Loma Linda University and Medical Center, and I am pleased to be able to represent us, and say a word about our institution when I attend these meetings. These awards are a tribute to the quality of work our group here at Loma Linda University does. It is an honor for LLU."26

8. Fighting Osteoporosis: David J. Baylink, MD

David J. Baylink (Class of 1957), Distinguished Professor of Medicine at Loma Linda University, directed the Musculoskeletal Disease Center at the Jerry L. Pettis Memorial Veterans Medical Center in Loma Linda. Dr. Baylink is one of the world’s leading authorities on osteoporosis, one of the most prevalent and costly diseases among the elderly.

Dr. Baylink belongs to many scientific organizations, including the American Society for Clinical Investigation, the American Association of Physicians, Alpha Omega Alpha, and the Czech Learned Society. He has received many awards for his work on bone and mineral metabolism, including the Medical Investigator Award, Veterans Administration, and has published more than 500 scholarly papers in the musculoskeletal field, including molecular genetics, tissue regeneration, and gene therapy.

9. Research to Benefit Open Heart Surgery: Brian S. Bull, MD

In 1975 three honors were awarded in 1975 to a six-member interdepartmental research team under the direction of Brian S. Bull (Class of 1961). At that time, he chaired the Department of Pathology.27 The team’s research demonstrated a method, which significantly increases the safety and success of open-heart surgery.28 During the surgery physicians administer heparin, an anticoagulant medication, used to prevent clotting of the blood. After surgery another medicine, protamine, neutralizes the effects of the anticoagulant. Anesthesiologists once followed strict guidelines based on the patient's weight and body surface area to calculate the heparin and protamine doses.

The Loma Linda University team concluded that the traditional weight/surface area method could lead to dangerous clotting or other hazards because of a wide variability in patient response. They developed a method of individualizing the medication dosage, depending on how a sample of the patient's blood responds to the heparin and protamine during the first few minutes of surgery. During their research the team developed mathematical calculations to plot an individual dose-response curve from which the correct doses could then be determined. (This process has since been computerized.)

The team prepared an exhibit describing these advances for the 1975 national meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Twenty-five scientific exhibits were accepted for display. Judged on the basis of their value in presenting new scientific concepts and methods, the LLU exhibit -- "The Laboratory Control of Heparin and Protamine Therapy in Cardiovascular Bypass" -- won first prize by a unanimous vote.

A paper by the same team ("Evaluation of Tests Used to Monitor Heparin Therapy during Extracorporeal Circulation") was selected for inclusion in the 1976 Yearbook of Anesthesiology, a compilation of summaries of the year's best articles published in the field of anesthesiology.

A third honor followed. A member of the team, Ralph A. Korpman, MD (Class of 1974), wrote the computer simulation program, received the Sheard Sanford Award. A student physician at the time, Korpman took first prize for the best research done during the year by a medical student in a University Department of Pathology. He received the award and presented his findings at the joint 1975 spring meeting of the American Society of Clinical Pathologists and the American College of Pathologists.

In 1990 Patricia M. Kopko, a junior medical student, received another Sheard Sanford Medical Student Award. The journal Radiology published her paper, "Thrombin Generation in Nonclottable Mixtures of Blood and Nonionic Contrast Agents"29 and accompanied it with a lengthy editorial declaring her paper to be of "critical importance."

Ms. Kopko's research helps physicians performing x-ray examinations of blood vessels to avoid potential complications. According to Dr. Bull, the singling out of a paper, by co-publishing it simultaneously with an editorial on the same topic, is an unusual honor accorded only to papers deemed to be highly significant. The American Society of Clinical Pathologists presented Ms. Kopko the award at its national fall meeting in Dallas, Texas, in October 1990.30

10. LLU’s Three Citation Classics

The scientific community's acceptance of research projects can be measured by the number of citations a research paper receives from other scientists in the same discipline. Every time another scientist refers to a particular paper in support of his own work, the citation is recorded by organizations such as the Science Citation Index (SCI). SCI thus identifies the papers that stand out in a particular field. Eventually, if a paper is cited often enough over a ten- to twenty-year period, SCI designates it as a Citation Classic. Three papers written by Loma Linda University faculty, all in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, have achieved this distinction.

- In 1958 Albert E. Hirst Jr., MD (Class of 1942), Department Chair (1963-1973), together with Varner J. Johns Jr., MD, and S.W. Kime Jr., MD, completed a paper entitled "Dissecting Aneurysm of the Aorta: A review of 505 Cases." This paper (Medicine 37:217-79, 1958.), is a collective review of 505 cases of dissecting aneurysm of the aorta, emphasizes historical aspects, clinical pathologic correlations, unusual manifestations, course, and treatment of the disease. The six-year project became a Citation Classic in July 1981.

- In 1965 Brian S. Bull, MD (Class of 1961) Chair, Department of Pathology, 1973-1994), together with M. A. Schneiderman and G. Brecher, described a method for the machine counting of platelets in human blood, using small samples of platelet-rich plasma. (American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 44:678-88, 1965.) The method included correction factors by which the resultant count could be transformed into a whole blood platelet count. It has rendered rapid and reproducible platelet counts with a minimum of technologist involvement, and thus has served the medical and scientific community well. This scholarly paper became a Citation Classic in October 1980.

- In 1968 Dr. Brian Bull, together with M. L. Rubenberg, MD, J. V. Dacie, MD (now Sir John Dacie), and M. C. Brain, MD, wrote a paper entitled "Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia: mechanisms of red-cell fragmentation: in vitro studies." This paper (British Journal of Haematology. 14:643-52, 1968.) describes how red cells fragment during inter-vascular clotting. With the use of a circulatory model Dr. Bull captured the instant of red-cell fragmentation on film. The paper's popularity may be due in part to its very graphic pictures of red-cell destruction. This paper became a Citation Classic in February 1986.

Inheritors of the Harveians: The Society of Scholars

In contemporary time, the Society of Scholars harks back to the Harveian Society in its zeal for research. It was established by the School of Dentistry during its 50th Anniversary celebration.31 It recognizes individuals who have contributed to the dental literature by writing chapters in leading textbooks or by authoring or editing textbooks. To be eligible for membership, a person must have participated in fifty or more publications.

Thirty individuals were named charter members of the Society of Scholars. Collectively they have authored 3,035 publications—an average of 101 per member. Four members have published more than 200 scientific articles:

- Philip J. Boyne, DMD, MS’61, Emeritus Professor, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery;

- James D. Kettering, PhD, Professor, Basic Science Faculty, School of Medicine,

- Anthony H. L. Tjan, DDS., PhD, Emeritus Professor, Restorative Dentistry, and

- Mahmoud Torabinejad, DMD, MSD, PhD, Professor and Director, Advanced Education Program in Endodontics.

A new display on the first floor of Prince Hall highlights these accomplishments, and exhibits forty-seven textbooks written by dental school faculty during the first fifty years.32

Ralph R. Steinman, DDS, MS, the first faculty member to publish fifty scientific articles acknowledged his membership in the Society of Scholars in a March 23, 2003 letter to Dean Charles J. Goodacre: “In 1951 I was called to work in God’s vineyard at Loma Linda. To me was given the joy of discovery. Thank you for honoring the results of that call.”33

To emphasize its Christian philosophy that the human body is the temple of God, Loma Linda University has chosen as its motto, “To Make Man Whole.” It seeks to restore man to wholeness, that he may more fully enjoy relationships with his fellowman and communion with God.

Our Research Has Now Arrived

“To Make Man Whole” must be more than a motto. It must be transformed into practical reality by continually developing new medical, surgical, and mental health services. Although Loma Linda University is perhaps best known as an educational center for Christian physicians and dentists, it is also known internationally in scientific and governmental circles for its contributions to medical, surgical, and dental research.

Much of this research, presented around the world in papers and scientific exhibits, deals with the basic sciences. Such research forms building blocks for future scientific breakthroughs. Most of the research, including today’s studies, is too technical to discuss here, but the contributions of the past represented by the research of Drs. Jorgensen, Hon, and Judkins, illustrate the major contributions to world medicine and dentistry that continue to be made by Loma Linda University staff and alumni. Today’s giants include Drs. Longo, Baylink, Slater, and Bailey.

For instance, Leonard L. Bailey, MD (Class of 1969), launched Loma Linda University Medical Center into international acclaim in 1984. Years of painstaking experience in his surgical research laboratory had preceded the honor. His infant heart transplant program not only captured the attention of the scientific world as well as the public, but it continues to add to the storehouse of knowledge and experience that saves lives and fosters hope.

In 1990 James M. Slater (Class of 1963), became the father of the world’s first hospital-based Proton Treatment Center. It also is known around the world for its scientific and technical prowess, as well as its compassion. Both men modestly emphasize that their contributions have resulted from team effort. It has evolved from cooperative collaboration with scientists and staff from within Loma Linda University as well as from external scientific consultants. These scientific breakthroughs, we can understand, have benefited from Loma Linda’s unique, more-than-100-year, daring-to-care heritage.

Section II: How We Are Doing It

Originally published in the Winter 2006 issue of Scope magazine as: The Emergence of Research at Loma Linda by Barry Taylor, PhD, Former Vice-Chancellor, Research Affairs

After the Santa Fe railroad reached Los Angeles in 1887, many new settlers from the East and Midwest came in search of a better lifestyle, health, and riches. A group of businessmen and physicians established a health resort on the hill at Loma Linda. They intended that it would be one of the finest among the many resorts developing in Southern California at the time.

After a struggle the place failed and was offered for sale at a discounted price of $110,000. A founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Ellen G. White, had seen in a dream a very attractive property on a hill. She envisioned it as a health resort for the Adventist Church. She had asked a minister, John A. Burden, to look out for such a property, and he was the one to locate the Loma Linda land. She later declared that it was the exact place she had first seen in her dream.

When the price of the seventy-six acre Loma Linda property dropped to 40,000, Pastor Burden received conflicting advice. Without consulting church leaders, Ellen White wrote: “Secure the property by all means, so that it can be held and then obtain all the money you can and make sufficient payments to hold the place. This is the very property we ought to have. Do not delay, for it is just what is needed…. We will do our utmost to held you raise the money.” Church leaders meeting in Washington, however, sent Burden a telegram: “Developments here warrant advising do not make deposit on sanitarium.”34

Burden accepted Ellen White’s advice and personally borrowed $1,000 for the deposit that secured the property. He knew that $4,000 would be due in one month. In two more months another $5,000 had to be paid. No one had any idea where that money would come from. Yet, when the payments came due, the Church received unexpected donations sufficient to cover the payments. Clearly, God was leading.

I. The Pre-Research Era (1906-1922)

To understand the history of research at Loma Linda University, one must recognize its historical context. The Adventist Church sought to establish a major health center and a health-related educational institution without the necessary resources. Although they were inspired by faith that God was leading, it was a constant struggle and the survival of the institution was often in doubt. On top of that, the Seventh-day Adventist denomination had been organized only forty years before the purchase of the Loma Linda property.

The Church was on fire with a mission to save the world. A mission that included a strong emphasis on training medical missionaries to serve the evangelistic goals of the Church. Research was not considered relevant to this enterprise. The faculty had little background in the traditional research that was characteristic of major universities.

The School of Nursing adopted the first educational program, followed in 1909 by a charter from the State of California for the College of Medical Evangelists. This measure established a School of Medicine—but no research. The new medical school received a Class “C” grade from the American Medical Association accrediting body in 1915. This rating made the students’ diplomas of little value. An upgrade to Class “B” in 1917 still called forth heavy criticism about the qualifications of the faculty.35

II. The Era of Freedom to Do Research (1922-1951)

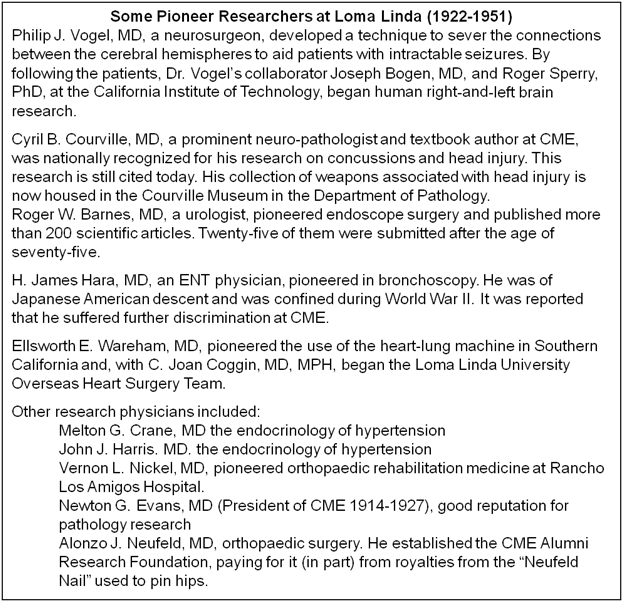

During this time, medical missionary training was still the main activity. Accrediting agencies, however, began to mandate that the fledgling medical school make plans to include research as a component of the CME academic program. As a result, individual faculty members who were passionate about research and who were able to do it with minimal resources were given the freedom to add research to their busy schedules.

Some faculty members made notable research contributions. Newton G. Evans, MD, President of the College Medical Evangelists (1914-1927) was a graduate of Cornell University School of Medicine. He and others recognized the importance of sending Adventist young people for training in major universities. As the quality of the faculty improved, CME received the much-desired Class “A” rating in 1922. Even so, in the letter from the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals, research was identified as an area of weakness. “You are undoubtedly already fully familiar with the fact improvements can be made with great advantage in the following particulars:… The making of adequate provision whereby medical research can be carried on.”36

Between 1930 and 1940 pressure to improve research continued to come from the accrediting body. Fred Zapffe, MD, of the Association of American Medical Colleges criticized CME for the lack of credible research programs: “It is the function of every medical school to teach and to do research, and I may add, to care for the sick in its hospitals. A teacher who has not been bitten by the research bug is not a real teacher. He merely passes on what he has read, which is not real education at all. Such teaching is being discouraged and even condemned more and more.”37

Pressure also came from a group of alumni who formed the Harveian Society. They advocated reform at CME. Percy T. Magan, MD, Dean of the School of Medicine, summarized attitudes to research in a letter to A. G. Daniells, (a Seventh-day Adventist church leader): “I have never felt that I could conscientiously and fairly, in view of the interest of the school, take a position that we would do no research work, but in a way I have looked upon this much the same…as I have looked upon accrediting with these worldly organizations. I have felt that it would undoubtedly be necessary to try to do a little along this line in order to keep the peace and keep our school from getting into trouble with the men who are at the helm of things medical in the United States. Nevertheless, in my soul I have had very little regard and fondness for this thing.”38

With research tolerated by most and encouraged by a few, some individual faculty members achieved distinction in their research during the 1940’s and 1950’s. They were mainly on the Los Angeles campus where students received clinical training for the MD degree. An additional boost to research was the access of CME clinical faculty to the broader world of medicine at the Lost Angeles County General Hospital. There they had contact with physicians from other medical schools.

III. The Era of Externally Mandated Research (1952-1961)

In this era medical missionary training was still the main activity, but the patience of the accrediting bodies ran out, and CME was unexpectedly placed under a mandate to demonstrate administrative support for research. The leadership team at CME responded positively. They actively recruited faculty with research training.

At the dawn of the 1950’s the Loma Linda campus of CME was known as “The Farm.” Little research occurred there. Raymond A. Mortensen, PhD, persevered on metabolic studies in animals. Raymond E. Ryckman, PhD, remembers when he, Bruce W. Halstead, MD, and Harold N. Mozar, MD, went to talk to Harold Shryock, MD. Dean of the School of Medicine. On the subject of research, he said: “Gentlemen, I cannot conceive of the day in which research will ever be conducted on the Loma Linda campus of CME. Maybe some at the White.”39

Two important events in Loma Linda’s research history, however, were about to change that idea!

The School of Tropical and Preventive Medicine. The first was the formation of a School of Tropical and Preventive Medicine (STPM) in the old South Laboratory. After World War II much interest in tropical medicine arose. Indeed, it was expected that U.S. medical schools would quickly develop expertise in this area. Dr. Harold Mozar had directed an Army School of Tropical Medicine in New Guinea, and Walter E. Macpherson, MD, then Dean of the School of Medicine, invited him to develop a School of Tropical and Preventive Medicine at CME. An upstart medical student, Bruce A. Halstead, was to be the Associate Director—while he continued what became his lifelong study of poisonous fish. Research and scholarly publications were prominent in the mission of the new school.40

Dr. Halstead became an internationally recognized expert in marine toxicology, and his three-volume treatise on poisonous and venomous marine animals is still a definitive work in this field today.

The STPM hired well and built a strong research team. Dr. Raymond Ryckman, a medical entomologist trained at the University of California, Berkeley, joined the team and obtained contracts with the Army to study various vectors. He became the foremost authority on Triatoma, the “kissing bug.” (It is the vector for Chagas disease.) This work is still highly important to public health in Central and South America. As a result, the Communicable Disease Center of the United States Public Health Service recently republished Dr. Ryckman’s dissertation, accompanied by an annotated bibliography of 23,000 references in Spanish French, Portuguese, and English. The World Health Organization helped fund this research.

Edward D. Wagner, PhD, a medical parasitologist, studied snails and their role in Schistosomiasis. George A. Nelson, PhD, improved the protocol of a Japanese scientist and became the first person to crystallize large amounts of tetrodotoxin. Thus he brought classified research to Loma Linda. He supplied the crystals to Robert Woodward, PhD, a Harvard chemist who determined tetrodotoxin’s structure—and went on to win the Nobel Prize in 1965.

A biochemist, U. D. Register, PhD, was the first to prove—scientifically—the nutritional adequacy of the vegetarian diet. This finding led the American Dietetic Association to stop listing the vegetarian diet as nutritionally deficient in amino acids.

The STPM made three more important contributions to research. First, they hired Milton Murray as a public relations officer and fundraiser, launching his illustrious career. Second, they were the first researchers at Loma Linda to obtain National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding. The formal peer review process we now associate with NIH, however, was not yet in place.

Mervyn G. Hardinge, MD, PhD, DrPH, appears to have been the first recipient of an NIH award under the peer review process. Third, the STPM also developed productive links to naval and army research funding offices.

Another Unfavorable Accreditation Report. In 1952 another less-than-satisfactory report from the Council on Medical Education stimulated change in research. They were dissatisfied with the attempts to upgrade the teaching of anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology. They insisted that CME look outside of the Adventist Church and hire experienced chairs for these departments. As a result, CME hired Otto F. Kampmeier, MD, PhD, in anatomy. Charles M. Gruber, MD, PhD, in pharmacology, and J. Earl Thomas MD, in physiology.41 These new chairs immediately improved the teaching of basic sciences and also worked hard to foster research. They received strong support from Harold Shryock, who readily embraced research after the 1952 accreditation report.

The new chairs worked cooperatively with CME to recruit well-trained Adventist basic scientists and then mentored them in both research and teaching. Drs. Kampmeier and Gruber were instrumental in starting the first PhD program.42 Early, well-known recruits included Dr. Mervyn Hardinge, who had received a DrPH at Harvard for his research on vegetarian nutrition. (He was then sponsored to Stanford University to get a PhD in pharmacology.) He subsequently took over as Chair of Pharmacology, where he led out in securing external research grant funding.

Later, Hardinge founded the School of Public Health with a strong emphasis on research. The growing research emphasis in the basic sciences in the 1950’s and 1960’s attracted many new faculty with research interests. They included Ian M. Fraser, PhD, and Leonard R. Bullas, PhD (both from Australia), R. Bruce Wilcox, PhD, Allen Strother, PhD, T. Joe Willey, PhD, and Brian S. Bull, MD.

Niels Bjorn Jorgensen, DDS, Professor of Oral Surgery, brought international recognition of the newly established School of Dentistry by pioneering research in a new technique of dental pain control. His contributions brought profound changes to dentistry and to undergraduate dental education. Lloyd Baum, DDS, developed techniques for improving gold foil fillings and specialized instruments. Robert A. James, DDS, was a pioneer in oral implantology (including the first description of the implant-tissue interface).

IV. The Era of Research Fostered (1962-1991)

On July 1, 1961, CME became Loma Linda University. The new university status was associated with a greater internal commitment to research as an intrinsic component of academic life. There was also a growing recognition of research as a “moral” obligation to contribute to the knowledge used in teaching and service. Questions were raised as to whether an emphasis on research was at odds with the religious mission of the University. In the discussions that followed, however, both Adventist Church leaders and the University community recognized that past research had been beneficial to the Church. Furthermore, medical research and basic research that explored “God’s handiwork” could only be seen as supportive of the mission of Loma Linda University. With this affirmation of research, centers of research excellence were begun. They flourished!

G. Gordon Hadley, MD, was an administrator who always fostered research. As a young man he had made an important finding that the addition of EDTA to a tube before a blood draw would prevent clotting. Today this method is commonly used. As Dean of the School of Medicine, he found a way to help passionate researchers get the equipment they needed.

Another administrator who enabled researchers in the basic science departments was Ian M. Fraser, PhD, initially Chair of Physiology and Pharmacology and later Vice-president for Academic and Research affairs. He fostered a culture of support that facilitated the growth of the research faculty.

The landscape on the Loma Linda campus changed after David B. Hinshaw Sr, MD, became Dean of the Medical School. He succeeded first in consolidating the newly named Loma Linda University School of Medicine on the Loma Linda campus. Then he sought out more research faculty. The illustrious list includes Virchel E. Wood, MD, an orthopaedic surgeon, who became renowned for pioneering surgery to treat congenital hand deformities. In 1995, he received an award as “the Most Frequently Cited Author in Congenital Hand Literature in the Past 50 years.”43

Melvin P. Judkins, MD, started the modern cardiac angiography era, came to Loma Linda University as Chair of the Department of Radiology. Because of his national reputation, he developed the strong patient base, so important to his continued research. At the same time, his work made a financial contribution to the new medical center in Loma Linda.

Lawrence D. Longo, MD, was recruited from the University of Pennsylvania in 1970. With his OB/GYN expertise, he formed the Center for Perinatal Biology (in affiliation with the Departments of Physiology and Pharmacology). Gordon G. Power, MD (1972) and Raymond D. Gilbert, PhD (1975) joined the team. By 1976 this center became one of the best perinatal biology programs in the United States. Well funded by NIH, it received LLU’s first program project grant from that organization (1985). Not only did the Center nurture other scientists and encourage collaboration with other faculty members, it also trained high-quality graduate students. Knowledge and expertise was shared generously.

Subsequently, other research centers were established at the VA Medical Center. W. Ross Adey, MD, studied the effects of electromagnetic radiation on biological organisms. David J. Baylink, MD, operated his mineral metabolism laboratory with its pioneering studies of osteoporosis.

The VA Medical Center research programs have contributed substantially to the expansion of research at Loma Linda University. Hired primarily for their research skills, the faculty have brought expertise in advancing fields that were not previously available to the University. Indeed, the VA faculty helped form a critical mass of highly trained basic science researchers. Through collaboration they provide excellent training for graduate students, with heavy teaching assignments in the biochemistry and physiology graduate programs.

.jpg)

Lifestyle Changing. In addition to the development of research centers in the School of Medicine, another important research program developed in epidemiology in public health. Starting in 1958, Frank R. Lemon, MD, and Richard T. Walden, MD, commenced a study of 65,000 Adventists in California, with funding from the National Cancer Institute. The study investigated lifestyle elements that contribute to coronary atherosclerosis. Later, the American Cancer Society funded the addition of cancer to the study.

A new cohort of Adventists was enrolled in a 1973 study headed by Roland L. Phillips, MD, and Jan W. Kuzma, PhD. This study, supported by the National Cancer Institute, is known as Adventist Health Study—1 (AHS-1). A grant to continue AHS-2 was awarded to Gary E. Fraser, MD, PhD, in 1992. In 2001 Dr. Fraser received $18 million for what is now known as Adventist Health Study—2 (AHS-2). Also noteworthy was the $4 million received by Synnove M. F. Knutsen, MD, PhD, and David E. Abbey, PhD, for studies of Adventists and the health risks of air pollution. These projects are among the landmark epidemiology studies supported by NIH.

.jpg)

Leonard L. Bailey, MD, followed this research with Baby Fae’s baboon heart transplant and the numerous successful infant heart transplants that were performed thereafter. This program still ranks first in the world.

James M. Slater, MD, pioneered proton therapy and developed the proton accelerator in Loma Linda University Medical Center. These high-profile successes brought prestige and enormous free publicity for the Medical Center and the University. Following the advances by Drs. Bailey and Slater, the attitude toward research changed when, and for the first time, LLUMC administration understood that research could be a financial benefit, not just a drain on the budget.

Wolff M. Kirsch, MD, a neurosurgeon, inventor, and basic scientist, established a Neurosurgery Center for Research, Training and Education. His team develops surgical devices and studies the role of iron metabolism in the onset of Alzheimer’s disease—all supported by a major award from NIH.

The success of those research centers led to a “centers of excellence” theme running through the School of Medicine. Policy directed that research resources would be focused in the centers, with departments primarily engaging in teaching. Thus, resources were targeted to investigators who were most likely to receive NIH funding.

V. The Era of Research as a Mission (1992-Present)

Although it was traumatic at the time, the 1990 separation of Loma Linda University and La Sierra University as distinct institutions proved to be highly beneficial to both universities. The re-organization of Loma Linda University as a health-sciences university brought focus and clarity to the mission of the University. In the discussions that preceded a revision of the mission statement for this campus in 1993, it was recognized that research should have a greater role in a health-sciences university. The new Loma Linda University mission statement boldly declares: “Loma Linda University, a Seventh-day Adventist Christian health sciences institution, seeks to further the healing and teaching ministry of Jesus Christ ‘to make man whole’ by…expanding knowledge through research in the biological, behavioral, physical, and environmental sciences and applying this knowledge to health and disease.”

The expanded emphasis on research was formalized in 2000 by the appointment of Barry L. Taylor, PhD, as the first Vice-president for Research Affairs. The next six years saw a doubling of the competitive research awards to the institution and a substantial expansion of the research services to support faculty endeavors.

Research in Dentistry. The Schools of Dentistry and Nursing also developed research strengths in departments or programs. Ralph R. Steinman, DDS (Oral Medicine) and John Leonora, PhD (Physiology) demonstrated a fluid transport system in teeth, wherein the pulp traveled through dentinal tubules. Their work resulted in the discovery of a new hypothalamic-parotid gland endocrine system that stimulated dental fluid flow.

Mahmoud Torabinejad, DDS, PhD, made major contributions to our understanding of the mediators of inflammation in perapical lesions of animals and humans. He also brought substantial royalties to Loma Linda University. These came from an irrigant he developed to disinfect root canals and a cement for sealing them. This became the material of choice for endodontists in America and Europe.

Research in Nursing. When former School of Nursing Dean, Helen E. King, PhD, RN, fostered doctoral and post-doctoral training for nursing faculty, she stimulated faculty research in the School of Nursing. Four NIH awards were forthcoming:

- Lois H. Van Cleve, PhD, RN. The study of pain and its management in children with leukemia,

- Michael E. Galbraith, PhD, RN. The study of the quality of life in men with prostate cancer,

- Patricia I. Jones, PhD, RN. Continued investigation of care-giving for elderly parents in various Asian cultures, and

- Betty W. Winslow, PhD, RN. The study of the family caregivers for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and the processes used to make placement decisions.

High Quality Graduate Programs at LLU Secure Excellence in Research

The emergence of high-quality graduate programs was an essential factor in research expansion at Loma Linda University. These included postgraduate programs in dentistry and the graduate program in epidemiology.

Barry Taylor rejuvenated the MD/PhD combined degree program in 1978. Then, in 1983, Robert Boucek, MD, and W. Barton Rippon, PhD, took graduate education to a new level of excellence with the medical scientist graduate program. For this project, leading researchers from the California Institute of Technology, City of Hope Medical Center, and other Southern California universities were recruited. They lectured on emerging areas of biomedical science and mentored graduate student research in their laboratories. Anthony J. Zuccarelli, PhD, subsequently gave leadership in this area. Later, the doctoral programs in psychology were strengthened by collaboration with the faculty of California State University at San Bernardino.

The pending retirement of the post-World War II generation of faculty posed a serious challenge to American universities in the 1990’s. The basic science departments at LLU experienced the same problem. This challenge provided an opportunity to hire faculty with excellent research training and productive post-doctoral fellowships—as well as a commitment to the University’s mission.

Many faculty and center directors were aided by tips from faculty at Adventist colleges, helped search for the most qualified individuals, irrespective of gender or ethnic heritage. Providentially, some well-trained persons of color, whose existence was generally unknown at Loma Linda University, were interested in the mission of the University, and eventually enquired about positions at Loma Linda University.

They also provided information about other scientists of color whom they knew and who had excellent research qualifications and an interest in the mission of the University. It was realized that many of the most qualified Adventist candidates for research faculty positions were people of color who had pursued education and employment outside of the Adventist system. Eventually hiring and retention of some of those individuals brought increased strength and diversity to the research efforts in several centers and departments and led to funding by the NIH for a “Center for Health Disparities Research,” directed by Marino De Leon, PhD, at LLU in 2005.

Research at Loma Linda University has continued to expand, and today the University receives almost $40 million per year for funded research programs. This expansion led to the appointment of Lawrence C. Sowers, PhD, as Associate Dean for Basic Sciences in the School of Medicine. There has also been an expansion of research services provided by the office of the Vice-president for Research Affairs. This includes aTechnology Transfer section that processes 200 research contracts per year and manages the intellectual property portfolio for the institution.

Some patents are now producing substantial royalties. The Research Integrity section was established to oversee compliance with the complex governmental policies that now regulate research. A human-studies educator now trains coordinators for clinical trials. The sections for Research Administration, Research Protection Programs, and Financial Management have been expanded to improve the workflow, and better coordination between the offices is now evident. Two Associate Vice Presidents now assist the Vice President in the management of the research program.

A cadre of well-trained and very talented younger faculty in setting high standards; there are now more than 100 principal investigators at Loma Linda University who receive funding from outside the University and Medical Center to support their research. This represents a healthy mix of center and departmental research that will continue to prosper, going far beyond the vision of our most farsighted pioneers.44

References:

[1] Marilyn C. Crane, MSLS, Associate Chair, Archives and Special Collections, Del E. Webb Memorial Library, Today, April 29, 1999, p. 5.

[2] In 1928 the Tercentenary of William Harvey’s classic Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus was celebrated

[3] Officers elected in the first year (1928) were: Cyril B. Courville, resident; Clement E. Counter (Class of 1925), Vice-president; G. Mosser Taylor, Secretary-treasurer; and Howard A. Ball (Class of 1928), historian.

[4] Charles B. Coggin was the father of Joan Coggin (Class of 1953-A) member of LLU Overseas Heart Surgery Team; Harveian Review of the College of Medical Evangelists, Devoted to Education and Research, College of Medical Evangelists, Loma Linda, California.

[5] The Harveian Society also issued the Collected Papers of Harveian Society Members, consisting of journal reprints by Society members from 1928 to 1938. An author, and sometimes a general subject index, is provided in each bound volume.

[6] March of CME. 1941, Student-Faculty Association of the College of Medical Evangelists, Los Angeles, California, p. 131.

[7] School of Dentistry Executive Committee, Minutes, September 10, 1956.

[8] Merlin D. Burt and Petre Cimpoeru, Oral history with David B. Hinshaw, Sr., MD, July 24, 1996, pp. 45-46.

[9] Dr. Jorgensen taught in the School of Dentistry between 1954 and 1974.

[10] Jess Hayden Jr, DMD, PhD, “The Limits of Excellence: What One Man Can Do,” Presented at the First Annual Niels Björn Jörgensen Memorial Lecture, February 29, 1976.

[11] Professor Leffingwell chaired the Department of Anesthesiology at CME/LLU School of Medicine between 1956 and 1968.

[12] Richard A. Schaefer, “To Make Man Whole,”Legacy, pp. 192-193.

[13] Loma Linda University Observer, August 29, 1974, p. 1.

[14] Loma Linda University Observer, August 29, 1974, p. 1.

[15] LLU Board of Trustees, Minutes, November 18, 1971, p.2. Just before his death (August 15, 1974) Dr. Jorgensen became a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. (LLU Board of Trustees, Minutes, August 22, 1974, p. 4.)

[16] Schaefer, "To Make Man Whole," Legacy, pp.190-191. “Obstetrics Goes Electronic: Automatic Monitoring Aimed at Assisting in Cases of Birth Complications,” Loma Linda University Magazine, October 1962), pp. 20-25.

[17] “Monitoring the Unborn,” Newsweek, October 21, 1968, p. 72; See also “Fetal-monitoring equipment installed in University Hospital, University Scope, December 11, 1968, p. 1.

[18] “Obstetrics Goes Electronic,” Loma Linda University Magazine, October 1962, pp. 20-25.

[19] “‘Watching’ the Unborn Inside the Womb,” Life, July 25, 1969, pp. 63-65.

[20] “Fetal-monitoring Equipment Installed in University Hospital,” University Scope, December 11, 1968, p. 1.

[21] Loma Linda University, Observer, Thursday, April 8, 1971, p. 1; Richard A. Schaefer, personal collaboration with Dr. Leonora.

[22] Richard A. Schaefer, “Unique Contributions Through Research,” LEGACY, pp. 233, 234.

[23] Richard A. Schaefer, “Unique Contributions Through Research,” LEGACY, pp. 233, 234.

[24] This legislation covered the hazards of smoking in relation to heart disease, lung disease, and problems for the pregnant woman and her fetus.

[25] Dr. Longo served as a scientific consultant to the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the National Research Council. He also serves on an advisory panel of the Environmental Protection Agency, which made recommendations leading to enactment of the Clean Air Act.

[26] “Dr. Lawrence D. Longo Receives Prestigious Awards,” Scope, Autumn 1996, p. 86.

[27] Between 1994 and 2002 Dr. Bull served as Dean of the School of Medicine.

[28] Richard A. Schaefer, “Unique Contributions Through Research,” Legacy, pp. 251- 252.

[29] In Radiology, Vol. 174, 1990, pp 459-461.

[30] In Radiology, Vol. 174, 1990, pp. 459-461.

[31] Charter members of the Society of Scholars include: Leif K. Bakland, DDS; Lloyd Baum, DMD, MSD; Gary C. Bogle, DDS, MS; Philip J. Boyne, DMD, MS, DSc.; Edwin L. Christiansen, DDS, MA, PhD; Noel M. Claffey, DD., MDS, MA; Ralph W. Correll, DDS; Jan H. Egelberg, DDS, LDS, MS; Ralph P. Feller, DMD, MPH; J. Steven Garrett, DDS, MS; Charles J. Goodacre, DDS, MSD; Robert A. James, DDS, MS; William T. Jarvis, MA, PhD, MPH; James D. Kettering, PhD, MS; Yiming Li, DDS, MSD, PhD; Jaime L. Lozada, DDS; Melvin R. Lund, DMD, MS; Carlos A. Munoz, DDS, MSD; W. Patirck Naylor, DDS; Rolf Nilveus, DDS; Richard C. Oliver, DDS, LDS, MS; Knut A. Selvig, PhD, DDS. MS; James H. S. Simon, DDS; Ralph R. Steinman, DDS, MS; Dimitris N. Tatakis, DDS. PhD; Anthony H. L. Tjan, DDS, MSD, PhD; Mahmoud Torabinejad, DMD, PhD, MSD; Leonardo Trombelli, DMD; Ulf M. E. Wikesjo, DDS, PhD; and Wo Zhang, MD, ADG.

[32] Dentalgram, March 2003, pp. 2, 4.

[33] Ralph R. Steinman, DDS, MS, Letter to Dean Charles J. Goodacre, March 23, 2003.

[34] Richard Utt, From Vision to Reality: 1905-1980. Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, California, 1980, p. 12.

[35] Utt, From Vision to Reality, p. 61; Carrol S. Small, Editor-in-Chief, Diamond Memories, School of Medicine Seventy-fifth Anniversary, Alumni Association, School of Medicine of Loma Linda University, 1984.

[36] N. P. Colwell, MD, quoted in From Vision to Reality, p. 62.

[37] Fred Zapffe, MD, quoted in From Vision to Reality, p. 89.

[38] Percy T. Magan, MD, quoted in From Vision to Reality, pp. 90, 91.

[39] Raymond E. Ryckman, PhD, Oral history with Barry L. Taylor, PhD, 2005.

[40] P. William Dysinger, MD, Health to the People: A History of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Loma Linda, 1905-2004. (Trafford: Publishing, 2007).

[41] Dr. Thomas later joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

[42] Ian M. Fraser, PhD, oral history with Barry L. Taylor, PhD, 2005.

[43] Robert L. Horner, editor, “Memories of thd Hand surgery Service,” AN INCREDIBLE JOURNEY ORTHOPEDIC SURGERY AT LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY IN THE 20TH CENTURY, Neufeld Society and Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda California, 92350, p. 59.

[44] Acknowledgements: I wish to thank Ian M. Fraser, PhD, who critically reviewed the manuscript and made helpful suggestions. The following have generously shared recollections with me: Raymond E. Ryckman, PhD; G. Gordon Hadley, MD, Bruce Wilcox, PhD, Lawrence D. Longo, MD, Ian M. Fraser, PhD, Gary E. Fraser, MD, PhD, Daniel Kido, MD, T. Joe Willy, PhD, Gary Fryckman, MD, Heritage Room, Loma Linda University Libraries.